Getting an electric vehicle while living in an apartment was a bit of an experiment. Public charging is still a bit rough around the edges, but it turned out manageable, and in fact quite cheap, with the help from some free charging. Here’s my experience with EV charging in the past six months.

From November to April I drove our Hyundai IONIQ Electric 3034 km (1885 mi) while keeping a charging log. I charged 37 times in total, on average from 56% to 92% state of charge. This covered various situations such as a small top-up to 100% before a long trip, a motorway fast-charge up to at most 80%, a full recharge after a long trip (the biggest being 11%->100%), and various city charging in between. Some of the charging sessions were tests to try out the various charger types and charging networks to get comfortable with the process.

Disregarding the tests, I charged on average every 100 km (62 mi). On long trips I gradually became more comfortable with going farther between charges, with the longest stretch being 263 km (163 mi) in the spring. But for city charging with a limited number of public chargers, it remains practical to charge when the opportunity arises, without running down to a low state of charge each time.

Charging in the City

Most charging sessions were on slow destination chargers, and most were in Aalborg where we live. We rely on public chargers as we live in an apartment and don’t have our own home charger. It works like this: Drive to a charger, find a free socket, plug in, and walk 10–20 minutes home or to work. Later, I walk back to pick up the car when I need it again, or when it’s done charging.

Remaining charging time at a slow charger.

Remaining charging time at a slow charger.

A home charger would be much easier to use, but for city dwellers with EVs, this is how it works at the moment (unless you drive to work and that workplace has chargers available). Each city and town will be different in the density, availability, and reliability of public chargers, and improving this infrastructure will be an undertaking for the next many years.

Going back and forth to the charger takes a bit of time, but the walk is healthy. However, driving in vain to find all charger sockets in use is annoying. For commercial chargers, you can usually look up their availability status online before going, but not all chargers are commercial, as we’ll get to later. In practice, sharing a limited number of public chargers takes a bit of foresight. If I know I’m going on a long trip, I start trying to charge up to 100% a few days in advance, so there’s time to come back later if the chargers are all in use the first time around. Another option would be to use fast-chargers (more) on the trip, but the IONIQ’s fast-charging speed is not as good as many other EVs in that regard.

Parking Problems

You shouldn’t block a public charger if you’re not using it — that is etiquette and usually also part of parking regulations. But it can also make using public destination chargers a hassle. If you plug in to charge late in the evening, it might be that the charging will finish in the middle of the night. Do you get up to move the car in the middle of the night? Do you skip charging altogether? (Probably not.) Do you pick up your car some time the next morning, hoping to get there before the parking attendant and other EV drivers in need of some juice? (Perhaps.) I try to plan my charging so I don’t block the charger unnecessarily, but it’s not always practical to do so, neither for me nor other EV drivers.

For EVs to become mainstream, I think the charging situation needs to become easier and require much less planning. As a start, the parking rules could be relaxed so the parking-only-while-charging requirement doesn’t apply at night. Ideally there should be enough parking spaces that you could leave your car some extra time after charging finishes while someone else could take over the socket you used. Such a grace period would also be helpful when you want to charge to 100%, because the car’s estimation of when the charging will finish can be a bit off.

Some EV parking signs in Danish. (Elbil is the Scandinavian word for electric automobile.)

Some EV parking signs in Danish. (Elbil is the Scandinavian word for electric automobile.)

In other situations, the parking time is limited. There is a parking lot in Aalborg where the two EV spots have a two hour limit but their charging sockets supply at most 11–12 amps. It’s nice to have a few parking spaces that are reserved for EVs, but with those sockets the charging itself is almost inconsequential since you add at most 15 km (9 mi) of range per hour. That’s like going to the gas station for only 1 liter of gas!

In another place they had 11 kW outlets and a three hour parking limit. That will get you far if your EV has a matching 11 kW on-board charger (OBC) which adds range at up to 60 km/h (37 mph). A plug-in hybrid/PHEV can also typically fill up its smaller battery completely in three hours. But for cheaper EVs with slow OBCs like the IONIQ, you’ll get at most 20 km/h (12 mph). I think something needs to be done here to improve the situation for social equality in EV adoption. The solution at Aalborg Zoo is nice: “No time limit while charging”. That way, all EVs get the opportunity to add meaningful range, while still not allowing blocking the parking spot unnecessarily. The last part just requires parking attendants to check the charging status and not just the parking disc. I’m not sure, but I have the impression that many parking attendants don’t yet understand or care about EV charging.

Another problem is when many of the public chargers are placed in expensive parking garages. It might be okay to use them once in a while when out of town, but when you live in an apartment and rely on local destination chargers in your daily life, you definitely don’t want to pay €15 for an eight-hour charging session — on top of the charging cost. Despite these problems, using an EV in Aalborg and Denmark works fine, and the charging has in fact been very cheap as we’ll get to soon.

Energy and Efficiency

In total I drove 3034 km (1885 mi) using an estimated 524 kWh of energy, or a bit less than 14 full charges of the 38.3 kWh battery pack. That comes out to 5.79 km/kWh (3.60 mi/kWh), or 17.3 kWh/100km (27.8 kWh/100mi). This was for the Danish winter half-year, using Continental AllSeasonContact tires, and my driving comprising 40% city, 20% open road, and 40% motorway. It also gives the average range of 222 km (138 mi) from a full charge for these conditions. As described in my previous post, efficiency and range depend heavily on speed and weather, so the results will be better in the summer. Also, some of the driving was economical but I also did a lot of unnecessary (but fun!) acceleration.

Economical driving from Odense to Aalborg, Denmark.

Economical driving from Odense to Aalborg, Denmark.

There are two things to add. First, the total energy is not only used while driving. The IONIQ, like regular cars, has a 12 V battery that discharges over time. The IONIQ, unlike regular cars, can keep the 12 V battery in shape automatically, using a bit of juice from the main driving battery. This will take around one percentage point of charge from the main battery per week, at least when it’s freezing. My calculated average efficiency and range includes half a year of parking, so during driving alone, the efficiency and range is a tiny bit better than the numbers above indicate.

Second, it’s not all the energy that comes through the charging cable that makes it to the battery. During charging, some electricity is lost as heat, plus the car needs some electronics running, and it might even spend energy on battery cooling or heating to optimize the charging speed, depending on the car model. The loss is around 10–15%. So getting 524 kWh into the IONIQ will actually have required around 600 kWh in total. Let’s see what this means for the cost.

Cost Complexity

EV charging prices vary a lot, at least in Denmark where legislation is complicated. Most EV price calculations I’ve read assume you will install a home charger, but for many city dwellers that is not an option, so I will instead exclude home charging. That removes some of the complexity of EV charging prices, including home charger installation, home charger purchase vs. rental, combined home and public charger subscription, time dependent electricity tariffs, electricity tax refunds, and interaction between tax refunds and the use of solar panels and geothermal heat pumps.

Public charging is still complicated, though: Pay per kWh or a fixed price per month, or somewhere in between. Use one provider, or multiple, or a meta provider, or somewhere in between. For fast-charging, the price can depend on the charging speed, or potential partnerships between EV manufacturers and charging providers. In some countries you also pay per minute.

You can also be lucky and have access to free charging. Our municipality has a few sockets in Aalborg for free EV charging, which is a nice “carrot” for EV adoption. Some hotels and supermarkets have free charging. For example, Lidl supermarkets have free chargers in some countries and are getting it in Denmark. Car manufacturers also sometimes offer some free charging. Hyundai started giving away six months of free charging with new leases, less than a week after we got our IONIQ. Tesla also sometimes gives away free charging.

Charging Cost in Denmark

As mentioned in the previous section, there are many possibilities. Here I will compare what I do with a few simple alternatives. Blessed with tax-paid electricity in Aalborg, I mainly use those free sockets when at “home” — a 15-minute walk from our apartment. When all the free spots are taken, or when out of town, I use the Clever charging network, with other networks such as E.ON, Spirii and Ionity as possible backups. Because I don’t use the commercial operators so much, it’s cheaper to pay by the kWh instead of using a flat rate subscription.

In the last six months I paid only 676 DKK (€91 or $111) for 191 kWh, while getting the remaining ~409 kWh for free. However, not everyone has the privilege (or patience) to use free charging, so I’m going to show some alternatives. Electricity prices and taxes vary by country, so I’m not going to convert the following prices as they are not directly comparable to other countries anyway. But here are the current prices in DKK/kWh for some charging network products and charger speeds (with Aalborg Municipality thrown in so you can see that my free charging is also slow charging):

| Charger power | Aalborg | Clever Go | E.ON Drive Lite | Spirii Go | Ionity (guest) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2–3 kW | 0.00 | - | - | - | - |

| 11–43 kW | - | 3.50 | 3.50 | 2.25–3.75 | - |

| 50–75 kW | - | 3.50 | 4.90 | - | - |

| 100–350 kW | - | 5.00 | 4.90 | - | 6.20 |

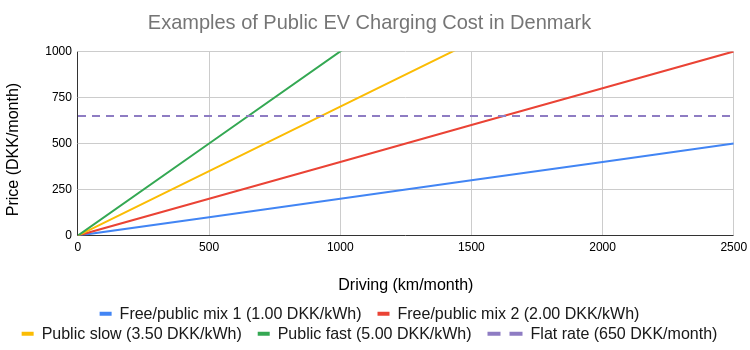

By mixing some of the above speeds and networks, you’ll end up with an average price per kWh. If you only use public chargers, you might end up at 3–5 DKK/kWh and if you can mix in free charging, you can get under 3 DKK/kWh. My average was just over 1 DKK/kWh for the past six months. I’m using these rates in the following graph, which also includes a typical 650 DKK/month flat rate subscription without a home charger included.

I made the chart based on a consumption of 5 km/kWh including charging loss, corresponding to the 5.8 km/kWh vehicle consumption that I got for the Danish winter half-year. In comparison, every time the Hyundai IONIQ drives 5 km, the Mercedes EQC will drive 4 km, and the Audi e-tron S Sportback will drive 3 km using the same energy. However, the majority of EVs fall somewhere between the EQC and the IONIQ — including Audi’s upcoming Q4 models, and the very-long-range Mercedes EQS.

The chart shows that what is cheapest depends heavily on your driving. Long-distance drivers will profit greatly from a flat rate subscription, while I would pay 5–6 times as much as I currently do. Before getting the IONIQ, I didn’t know it would end up like this — I just knew I wanted to support the push toward a greener future (and try out some cool tech while at it). And while charging turned out way cheaper than gasoline, the total cost still could have been lower by choosing a conventional car with a weaker internal combustion engine and a manual transmission. But for comparable cars driving an average 20,000 km/year or 16,000 mi/year, EVs already have ample opportunity to have a lower total cost of ownership in Denmark as well as the USA.

Update 2021-06-26, 2023-06-21: Minor fixes.